撤退的图像 The Recessive Image

薛涵天 Hantian Xue

莎丽・曼 (Sally Mann) 曾经在一次采访中形容数码图像为 「永不接触地面的蒸汽......它以无形的姿态环流,且不具有物质上的现实。」

从摄影诞生初始,人类对于这一媒介的本能敌意就已经表露地相当直接:照片——无论是曾企图彰显工艺品质的照片还是力图以像素仿写真实的照片,都是难以被信任的,这似乎形成了一种跨越时代的共识。但是我们与它的关系绝不仅限于此;在适当的条件下,我们仍然选择将照片或图像的在场作为一种现实世界中有形踪迹的判定标准,而能欣然忽略它背后潜在的陷阱。事实上,似乎一段有图像记录的历史永远都比没有视觉资料的历史更有 「被铭记」 的特权。

在摄影普遍呈数码化的时代,「照片」(Photograph)与 「图像」(Image)两者的界限变得更加模糊。我尝试从近些年刑侦领域的研究来观察这一点觉得很有意思。参考 《刑事诉讼法》 中我国法律规定允许的八种类型证据,其中最具有决定性意义的是物证、书证以及人证,他们记录的分别是静态事实与动态事实:常在性事实只能存在于物,因而构成物证;即逝性事实被图像记载时为书证,被人物感知时即为人证。

通常意义上,图像是归属于书证类别的材料,多数情况下它是有实体且被认为有能力客观记录现实的。但随着技术上的开拓以及材料媒介不可避免的多样化,又渐次产生了 「视听资料」 等备受争议的证据类别,它包括实体过程制作的录音、录像与电子计算机记录,也包括了办案过程中产生的 「高科技图像」 ——借助激光、红外或X光等精密仪器所得到的所谓模拟图像。稍加思索,就会发现其中提到的这些 「模拟图像」 本身似乎并非是 「模拟」(CT 拍摄的难道不是真实的身体吗?)他们记录的当然是一种现实,但这是我们无法利用双眼去穿透的现实。同理,如果使用激光与X光的拍摄器械属于精密仪器,那么相机某种程度上也具有同样的 「高科技」 素质。

浏览近几年刑侦领域的论文,会发现越来越多借助全新科学技术被呈现的类似取样尝试。其中有一项技术在多个论文中被提及,即通过图像拼接(Image Stitching)的方式来对有曲面的物证表面进行二维高分辨率采集。如此一来,不仅仅是照片与图像,物与图像之间的关系和界限也会发生变化。这套被采集出来的平面图像最终又该作书证、物证还是视听资料被采纳呢?

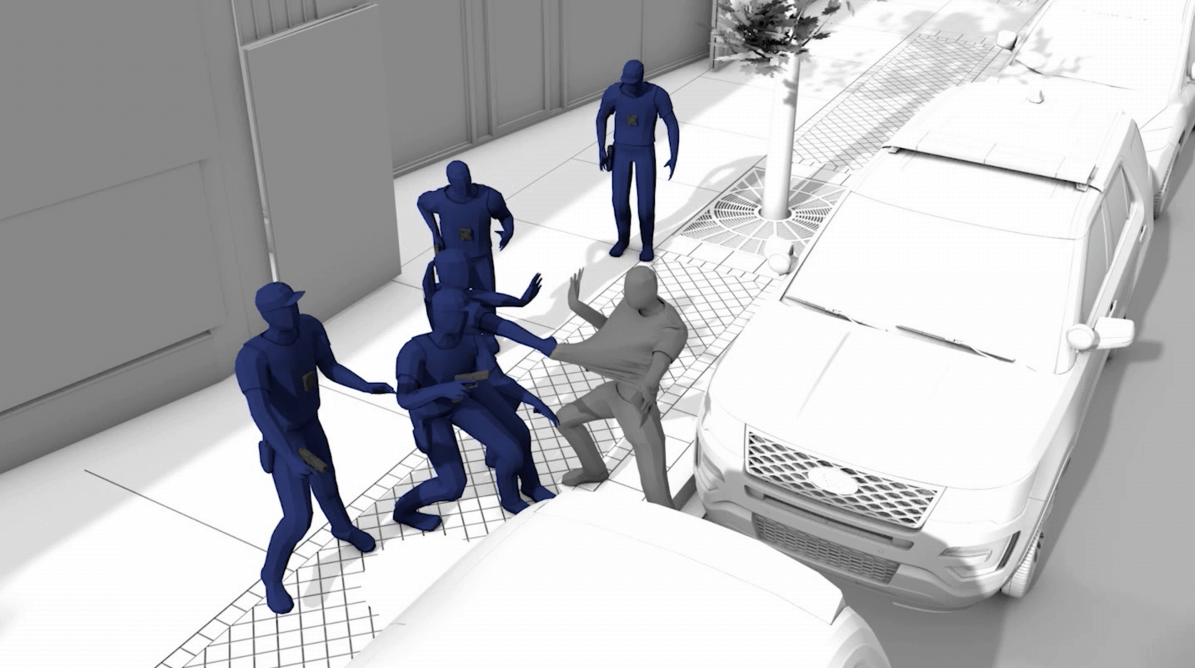

![]() The Killing of Harith Augustus-Milliseconds, Still from Forensic Architecture, 2020

The Killing of Harith Augustus-Milliseconds, Still from Forensic Architecture, 2020

利用刑侦证据作为探索切入点的原因很简单,因为它无法做到像当代艺术理论那样对材料所呈现的内容与形式保留足够的宽容余地,它对于证据是否可信的判断会即时导向一个具体的结果,但这套仰仗理性操作的程序并不是总能做出正确的裁判。我们常常感觉到它们对于图像的理解是如此受限,或者说是有些许错乱在其中,恰似我们历史以来与摄影技术之间那些始终无法落地的纠缠。既想利用它摹刻和证明真实,又打心底里畏惧它对我们的隐瞒。或许摄影的本质确如莎丽・曼(Sally Mann)和罗兰・巴特(Roland Barthes )所说——它是一个接近于幽灵的存在,透明、飘渺、不可视也无从定义。

![]()

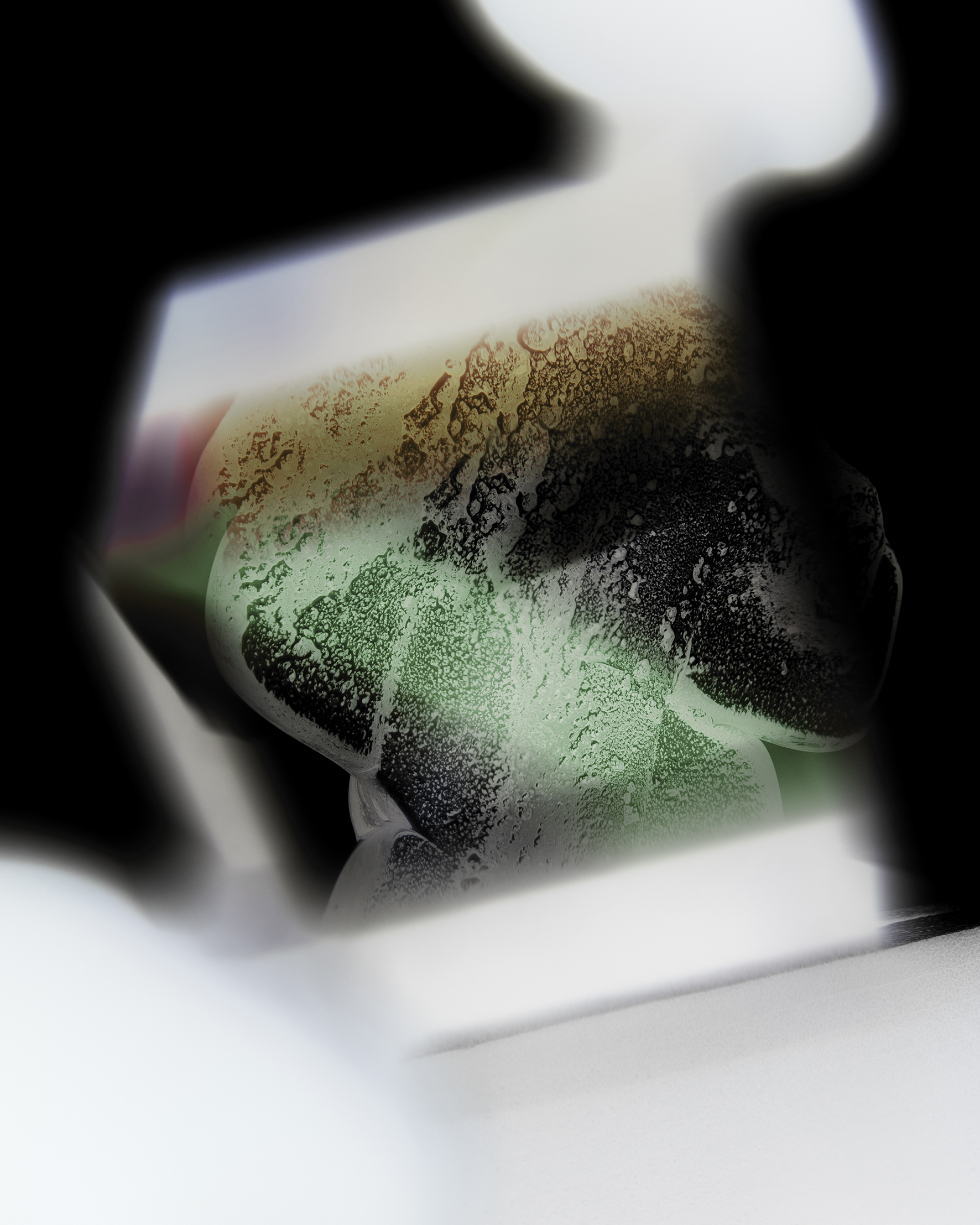

武雨墨, 透明攝影第十七張,溢出的溪流 (Spilling Brook), 透明摄影(The Transparency Photography), 2020

这也是我从武雨墨2019 年开始创作《透明摄影》(The Transparency Photography)系列开始,我在她的作品中逐渐发掘到的她对图像的个人领会。我想 「透明」 在这里并不是形容词,而是以名词形式出现是有原因的——并不是 「透明的」 摄影,而是摄影本身就是透明。

我们在这里提到的 「透明」 的概念与肯德尔・沃尔顿 (Kendall Walton)所认为的摄影是一种具有 「透视现实能力的媒介」 这一观点有本质区别,或者说它实际上更接近罗兰・巴特(Roland Bathes)在 《明室》(Camera Lucida)一书中提到的 「放射性物质」(Emanations)——它正在从明确的物理形态及意识形态中无限撤退,却始终为那些企图观看它的人带来困扰。正因为它给我们的是一种被文明所驯化的完美幻觉(Civilized code of perfect illusions), 这给摄影这门技术赋予了精神分析意义上的 「他者」(Other)的品质,摄影是为弥补和愈合欲望中那个永恒的伤口而生。

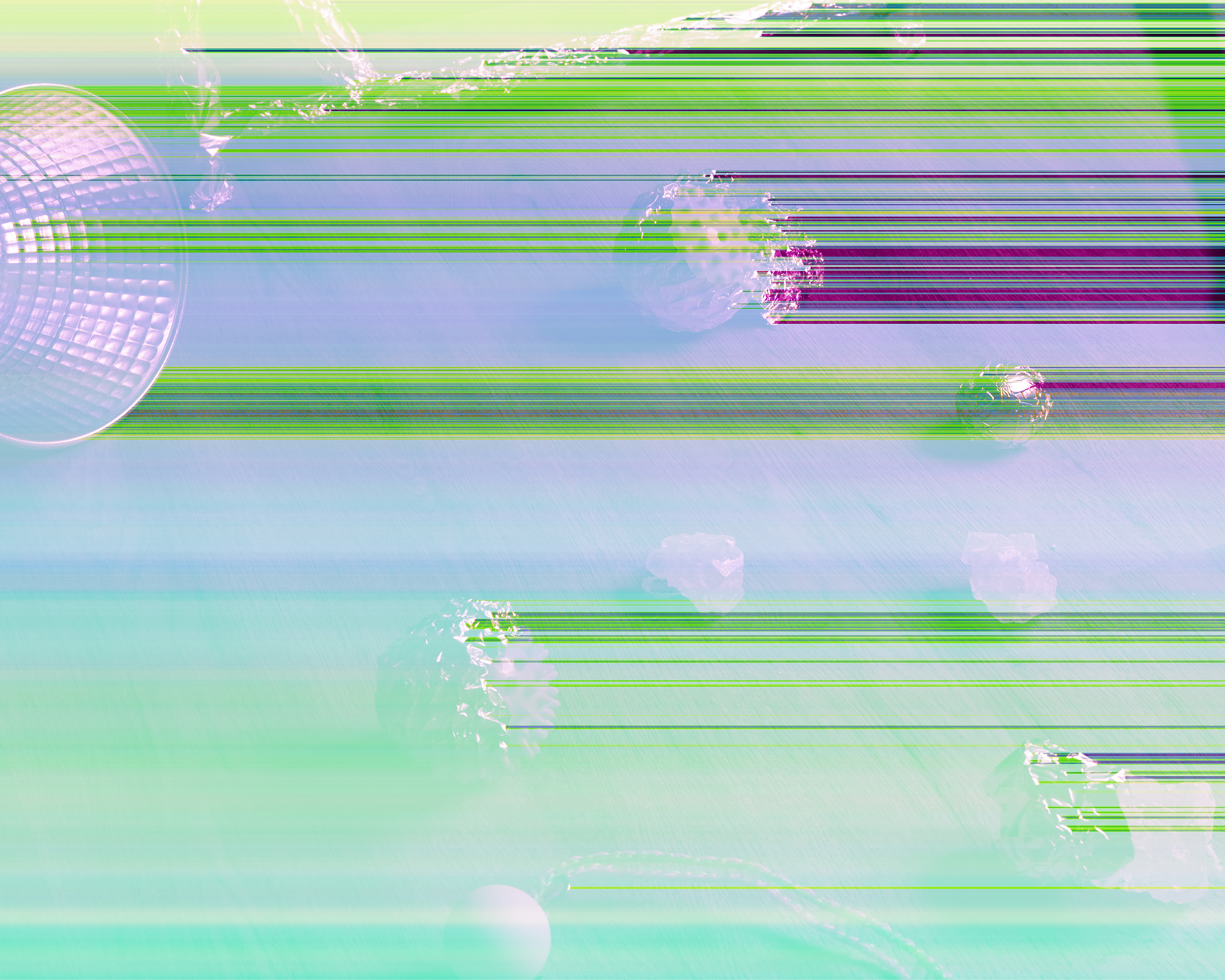

![]() 武雨墨, 透明攝影第十一張,颤抖的殘存像素 (Trembling Residual Pixels), 透明摄影(The Transparency Photography), 2020

武雨墨, 透明攝影第十一張,颤抖的殘存像素 (Trembling Residual Pixels), 透明摄影(The Transparency Photography), 2020

在《透明摄影》(The Transparency Photography)和《错误照相片》(Photographs with Errors)中,身为 「照片」 本应诉说的形象意义被搁置,但作为 「图像」 极为突出的数码材料属性放大了它们的制作过程并将数码相机独特的媒介特质展露无疑。在摄影仍然处于银盐感光的时期,我们就见证了摄影师们对其媒介属性的革命性探索,以同绘画媒介的不可复制性相抗衡。回到如今的数字摄影时代,艺术家们就像苏珊・史都华(Susan Stewart)所说的那样开始对手工显像的独一性和工艺品质感到怀念(光是看看现在的照片调色软件有多么钟爱 「胶片感」 就明白了)从而抗拒像素图像的千篇一律和操作性上惊人的便捷...简而言之,这是对摄影技术趋向民主化与平民化的潜在恐慌。

武雨墨在这两个系列中却顺应着这样的操作转而放大数码摄影中的电磁质感,原本应该是高保真、高视觉转化率的图像在这里成为了 「错误的图像」 ——作为照片而言它是 「失败的」 ,因为它不能够清楚地传达出那种得以摹刻现实的直感性(Immediacy)以及可信性(Credibility),但它透过刻意营造的错乱直指向了当代摄影的另一种工艺模式。尤其是在电子材料质感上,我感觉到它们不仅并不拥有 「错误」 中常见的廉价钝感,反倒是惊人的细致与准确。图像经由计算机被处理的过程通过手动拦截而变得透明,原应作为整体出现的图像受此干扰遭到拆解和异化,变成了难以被直观解读的断层。

![]() Catherine Yass, Descent: HQ2: ?s, 20°, 0mm, 4mph, south, 2003

Catherine Yass, Descent: HQ2: ?s, 20°, 0mm, 4mph, south, 2003

卡瑟琳・雅斯(Catherine Yass)在2002 年创作的系列作品 《下降》(Descend)曾就类似的主题进行过探索,在911 事件的政治阴霾下,她利用扭曲、反转、颠倒、长曝光和物理剐蹭等手段拍摄的影像不可避免地带有一种悲剧性的色彩:我们是否还能做到在看见一栋新建成的摩天大楼的同时不去想象它落为废墟的景象?正如后摄影时代的我们在网络上面对电子图片的时候,还有没有可能将它视为一个独立的、不具备目的与指涉性的对象(又或者我们真的曾经有过吗)?

![]()

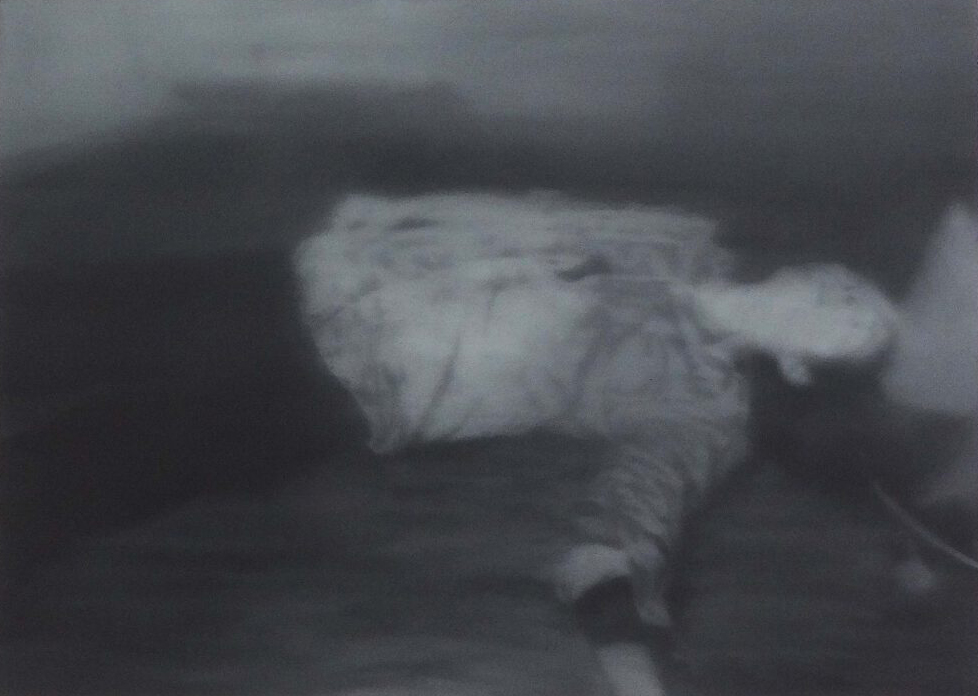

Gerhard Richter, Erschossener 1, 1988

进一步仔细观看,武雨墨的许多幅作品中依旧保留了可见的手工绘制痕迹,这一点不由令人联想到杰夫・沃尔(Jeff Walls)的 《障碍物》(The Stumbling Block)与葛哈・李希特(Gerhard Richter)的 《枪击》(Erschossene),前者是将多张编导过的 「纪实摄影」 通过电脑合成绘制的 「数字蒙太奇」(Digital Montage),而后者则是画家将刊登在报纸上的照片手工摹画下来的油画作品。这两幅作品的媒介全然不同,却同时表现出了身为图像对于被视为指示性符号(Indexical Symbol)的严词拒绝。

对武雨墨而言,这样的 「抗拒」 也是她创作的核心之一。她的照片中试图去展示的并不是任何对象,而是作为对象的摄影,与那些试图去凝视与解析它的观者。似乎只有当一件事物发生了故障和错乱,它内部真正的运行机制才有机会被揭露。 让・鲍德里亚 (Jean Baudrillard)认为摄影是一种 「完美的罪行 」(Perfect Crime),正因为它仅仅代表了我们欲见之物的表征,一个没有上下文的空洞的符号。如果我们去尝试揭开这一层意义,只会发现它所指向的虚无是经不起推敲的。

弗洛伊德的理论中对于 「错误」 有一番独到的认知,他认为对梦境或潜意识的解读永远都是碎片式的,在这些层面中精神分析师所阐释的往往是细节,而非整体。从一开始,他就将人的精神领域视为一种合成性的存在,这一点似乎能够引导我们更加深入地去理解武雨墨对于图像的态度。文章开头提到的图像作为刑侦证据的部分恰好说明了即便是最追求客观事实的科学,也难以回避 「透过假象进入隐含现实」 的陷阱。在摄影的历史中我们似乎总是在面对各式各样假象的挑战,无论是塔尔博特和尼埃普斯的时代还是杰夫・沃尔(Jeff Walls)与沃尔夫冈·提尔曼斯(Wolfgang Tillmans)的时代,它都是以可疑的方式在突破我们的认知,我们向摄影索求的真实仿佛一直被掩藏在暗房、计算机或是那些不能见光的原始文件当中。

武雨墨从2015 年开始就对 「负片」 的概念非常敏感,对于学习过胶片摄影的人来说,第一次在暗室里触摸到负片的实体其实都是颇为震撼,几乎带有一些宗教性质的体验,因为它经常被人认为是一张照片还尚未现形时的待定形态,而不是照片本身,这一点或许有点类似透过B超看见了胚胎的心脏在跳动的感受吧。乔夫里・巴钦(Geoffrey Batchen)在 《负像/正像:一部摄影的历史》(Negative/Positive: A History of Photography) 这本书中很深入地探讨了摄影史中负片与正片之间微妙的地位差异和互生关系,其中他引用了拉里·沙夫(Larry Schaff)的一句话 「从理化的角度而言,塔尔博特作品中的负片与正片之间并无本质区别;后者不过是前者的负片罢了。」 实际上不仅仅是塔尔博特,对于所有照片而言这种正负之分都是带有一种政治性偏见的。

![]()

武雨墨, 曬黑的痕跡(The Tanning Traces), 视觉的断裂(The Rupture of Vision)2021

人眼在看见负片的同时会屡次试图将它反转,在武雨墨 《视觉的断裂》(The Rupture of Vision)系列中的第一张照片里能够非常直观地感受到这种本能。第一眼我们看到像火箭一样拔地而起、带有突破形态的黑色粉末状物质,需要经过大脑的过滤才能意识到这是喷泉的水柱而不是爆炸带起的尘土。然而这张照片之所以令人惊愕,是因为它不同于其他的负片,它是一张乍眼看起来像正片的负片,两者的边界在大脑短暂的处理过程中被撤销了。

实际上,如果让弗洛伊德来解读正负片的关系,他会倾向于认为负片呈现的图像才是 「真实」 ,而那些被无限拓印的正片拷贝才是威胁所在。齐泽克说人类是唯一能够通过真话来行骗的动物,因为有些时候我们期望真话能够被当成谎言,这样一来我们便不必回应它的凝视。当我们必须要借助反转才能直面和识别一张图像时,应该对此感到警惕:非要如此阐释不可的动机是什么?我想这才是负片,乃至于任何被认为是 「错误的」 图像带给我们的本质意义。

所谓的数字艺术带来的伦理上的威胁,真的有如过去半个多世纪的想象中那样具有颠覆性吗?我们站在一个进退两难的节点——这是 「后摄影」 时代,但摄影的困境却好像从未被真正克服,也许应该换个方向撤退一步,再撤退一步,站在过去那些最原始的差错中去辩证和超越此刻它为我们带来的眩晕。

“The digital image", Sally Mann once suggested in an interview, "is like vapour that never comes to ground. It simply circulates, bodiless. It has no material reality".

From the very beginning of photography, the instinctive hostility of humans to this medium has been revealed quite directly: photographs, whether those that have attempted to show the quality of craftsmanship or those that seek to imitate reality in pixels, are difficult to trust. This seems to have formed a consensus that transcends the ages. But the relationship between people and photographs is by no means limited to this; under the right conditions, we still choose to take the presence of photographs or images as a criterion for determining tangible traces in the real world, while readily ignoring their potential pitfalls. In fact, it seems that a period of history with image records always has more privilege of being “remembered” than that without visual materials.

In the era of digital photography, the boundary between "photograph" and "image" has become more blurred. I attempt to observe this point from the research in the field of criminal investigation in recent years and find it very interesting. Among the eight types of evidence in the Criminal Procedure Law of China, the most decisive are physical evidence, documentary evidence and testimony of witnesses. They record either static facts or dynamic facts: permanent facts can only exist in objects and thus constitute physical evidence; transitory facts recorded by images are documentary evidence, while transitory facts perceived by people are testimony of witnesses.

In a general sense, images fall under the category of documentary evidence. In most cases, they are physical and are considered capable of objectively recording reality. However, with technological advances and inevitably diverse media materials, controversial evidence categories such as “audiovisual materials” have gradually arisen. These include audio and video produced by physical processes, electronic computer records, as well as “high-tech images” generated during case handling—so-called simulated images obtained with the help of laser, infrared, x-ray and other sophisticated instruments. On reflection, it seems that the "simulated images" mentioned are not "simulations" per se. (Aren't CT images of real bodies?) What they record is certainly a reality, one that we cannot penetrate with our eyes. Similarly, if shooting devices using laser and x-ray are considered sophisticated instruments, then cameras also have the same “high-tech” attributes to a certain extent.

Peruse papers in the field of criminal investigation in recent years, and one will find more similar sampling attempts presented with the help of new scientific techniques. One of the techniques mentioned in several papers is image stitching for the two-dimensional high-resolution acquisition of curved evidence surfaces. In this way, not only photographs and images, but also the relationship and the boundary between objects and images will change. Should this set of collected flat images finally be adopted as documentary evidence, physical evidence or audiovisual materials?

The reason for using criminal investigation evidence as an entry point for exploration is simple—it cannot retain sufficient latitude for the content and form presented by materials as contemporary art theory does, and its judgment of whether the evidence is credible leads instantly to a specific result. However, this procedure, which relies on the operation of reason, does not always deliver the right verdict. We often feel that its understanding of images is rather limited, or that there is a sense of ambiguity, just like the historical tangle that has always remained unsettled between us and photography. As much as we want to use photography for recording and proving the truth, we dread what it may conceal from us. Perhaps the essence of photography is indeed as Sally Mann and Roland Barthes have said: it is a presence close to a ghost, transparent, elusive, invisible, and indefinable.

This is also the personal understanding of images that I have gradually uncovered from Wu's work since she began working on "The Transparency Photograph" series in 2019. I think there is a reason for not using the adjective "transparent" here but the noun form - instead of "transparent" photography, photography itself is transparency. The concept of “transparency” we mention here is fundamentally different from Kendall Walton's idea that photography is a “supremely realistic medium”, or we can say it is actually closer to the “emanations” mentioned by Roland Bathes in Camera Lucida. It is retreating indefinitely from distinct physical forms and ideologies, yet it always bothers those who attempt to see it. Precisely because it brings us a civilized code of perfect illusions, photography is endowed with the quality of "other" in the psychoanalytic sense, which is created to mend and heal the eternal wound of desire.

In "The Transparency Photography" series, the figurative meaning of photographs is set aside, but the prominent properties of digital materials as "images" magnify their production process and reveal the unique features of digital cameras as a medium. At a time when silver salts were used in photography, we witnessed a revolutionary exploration for the properties of this medium by photographers to counter the irreproducibility of the painting medium. Fast-forward to today's digital photography era, as Susan Stewart put it, artists are becoming nostalgic for the uniqueness and craftsmanship of photographic films. (Just look at how many people favor the “film style" function in photo editing software these days.) They come to resist the uniformity of pixel images and the amazing ease of operation... In short, this shows an underlying fear of the democratization and popularization of photography.

In these two series, Wu follows this kind of operation to amplify the electromagnetic texture of digital photography. High-fidelity and high-resolution images turn out to be “wrong images” here — as photographs, they are “failures” because they could not clearly convey the kind of immediacy and credibility that can imitate reality, but they point directly to another process pattern of contemporary photography through deliberate confusion. In particular, when it comes to the texture of electronic materials, I find that they do not feature the common "mistake" of cheap bluntness but are instead surprisingly detailed and precise. The images processed by computers are made transparent by manual interception. They are supposed to appear as a whole but are disassembled and alienated by this disruption and turned into layers that are difficult to interpret intuitively.

Catherine Yass's 2002 series “Descend” explored a similar theme. Under the political haze of the 9/11 attacks, images she shot using distortions, reversals, long exposures and physical scratches inevitably had a tragic color: can we see a newly built skyscraper without imagining it falling into ruins? Likewise, when we see an electronic image online in the post-photographic era, can we view it as an independent object without purpose or indication (or did we ever have one)?

On closer observation, many of Wu's works still retain visible traces of hand-painting, reminiscent of Jeff Walls' "Stumbling Block" and Gerhard Ritcher's "Erschossene". The former is a "digital montage" that combines several edited and directed "documentary photographs" via computer, while the latter is an oil painting in which the painter drew a newspaper photograph by hand. The mediums of these two works are completely different, yet they both manifest a rigorous resistance to images being seen as indexical symbols.

For Wu, this kind of “resistance” is also at the core of her creation. What she aims to show in her photographs is not any object but the photography as an object and the viewers who attempt to gaze at and interpret it. It seems that only when something breaks down and goes wrong does the real mechanism of its inner workings come to light. Jean Boudrillard considers photography to be a "perfect crime" precisely because it is merely a representation of what we want to see -- an empty symbol without context. If we seek to unravel this layer of meaning, we might only find that the nothingness it points to cannot stand up to scrutiny.

Sigmund Freud's theory has a unique understanding of "mistakes". He believed that the interpretation of dreams or subconscious is always fragmented. In these levels, psychoanalysts often interpret details rather than the whole. From the beginning, he viewed the human spiritual realm as a synthetic entity. This point may guide us to understand Wu’s attitude towards images in greater depth. As is shown in the part of images as criminal investigation evidence mentioned at the start of this article, even the most fact-oriented science can hardly avoid the trap of "entering the implied reality through illusions". In the history of photography, it seems that we are always challenged by various illusions. Whether it's the age of Talbot and Niepce or the era of Jeff Wall and Wolfgang Tillmans, it's breaking through our perceptions in dubious ways. The reality we seek from photography seems to be hidden in the darkroom, in the computer, or in the raw files that cannot be seen.

Wu has been acutely sensitive to the concept of “negative films” since 2015. For those who have studied film photography, touching a negative for the first time in the darkroom is indeed shocking. The experience almost has a religious ring to it, as a negative is often perceived as the pending form of a photograph that has not yet taken shape, rather than the photograph itself. This is probably a bit like seeing the embryo's heart beating through ultrasound. In his book Negative/Positive, Geoffrey Batchen delves into the subtle differences in status and the symbiosis between negative and positive films in the history of photography. He quoted Larry Schaff as saying, “From a physical-chemical point of view, there is no essential difference between a negative and a positive in Talbot’s work; the latter is merely a negative of a negative." In fact, not only for Talbot's work, but for all photographs, the positive and negative distinction is politically biased to some extent.

When seeing a negative, human eyes will repeatedly try to reverse it. For example, you can clearly feel this instinct with the first photo of Wu's "The Rupture of Vision" series. At first glance, we see a black powdery substance that rises up like a rocket with a breakthrough pattern, and it takes a brain filter to realize that it is a fountain of water rather than dust brought up by an explosion. But what makes this photograph astonishing is that, unlike other negatives, it is a negative that at first glance looks like a positive, as the boundary between the two is withdrawn in the brief processing of the brain.

In fact, if Freud were asked to interpret the relationship between positive and negative films, he would tend to think that the images presented by negative films are "real", while the infinite positive copies are the threat. Slavoj Žižek said that humans are the only animals that can deceive through truth, because there are times when we expect the truth to be taken as a lie so that we don't have to respond to its gaze. When we have to use reversal to confront and identify an image, we should be wary of this: what is the motive for this interpretation? I think this is the essential meaning of what negative films, and indeed any image that is considered "wrong", brings to us.

Is the so-called ethical threat posed by digital art truly as disruptive as imagined over the past half century? We are on the horns of a dilemma—this is the post-photographic era, but it seems that the plight of photography has never been completely overcome. Perhaps it is time to retreat one step in a different direction, and then another, to stand in the most primitive mistakes of the past to analyze and transcend the dizziness it brings to us at this moment.

从摄影诞生初始,人类对于这一媒介的本能敌意就已经表露地相当直接:照片——无论是曾企图彰显工艺品质的照片还是力图以像素仿写真实的照片,都是难以被信任的,这似乎形成了一种跨越时代的共识。但是我们与它的关系绝不仅限于此;在适当的条件下,我们仍然选择将照片或图像的在场作为一种现实世界中有形踪迹的判定标准,而能欣然忽略它背后潜在的陷阱。事实上,似乎一段有图像记录的历史永远都比没有视觉资料的历史更有 「被铭记」 的特权。

在摄影普遍呈数码化的时代,「照片」(Photograph)与 「图像」(Image)两者的界限变得更加模糊。我尝试从近些年刑侦领域的研究来观察这一点觉得很有意思。参考 《刑事诉讼法》 中我国法律规定允许的八种类型证据,其中最具有决定性意义的是物证、书证以及人证,他们记录的分别是静态事实与动态事实:常在性事实只能存在于物,因而构成物证;即逝性事实被图像记载时为书证,被人物感知时即为人证。

通常意义上,图像是归属于书证类别的材料,多数情况下它是有实体且被认为有能力客观记录现实的。但随着技术上的开拓以及材料媒介不可避免的多样化,又渐次产生了 「视听资料」 等备受争议的证据类别,它包括实体过程制作的录音、录像与电子计算机记录,也包括了办案过程中产生的 「高科技图像」 ——借助激光、红外或X光等精密仪器所得到的所谓模拟图像。稍加思索,就会发现其中提到的这些 「模拟图像」 本身似乎并非是 「模拟」(CT 拍摄的难道不是真实的身体吗?)他们记录的当然是一种现实,但这是我们无法利用双眼去穿透的现实。同理,如果使用激光与X光的拍摄器械属于精密仪器,那么相机某种程度上也具有同样的 「高科技」 素质。

浏览近几年刑侦领域的论文,会发现越来越多借助全新科学技术被呈现的类似取样尝试。其中有一项技术在多个论文中被提及,即通过图像拼接(Image Stitching)的方式来对有曲面的物证表面进行二维高分辨率采集。如此一来,不仅仅是照片与图像,物与图像之间的关系和界限也会发生变化。这套被采集出来的平面图像最终又该作书证、物证还是视听资料被采纳呢?

The Killing of Harith Augustus-Milliseconds, Still from Forensic Architecture, 2020

The Killing of Harith Augustus-Milliseconds, Still from Forensic Architecture, 2020利用刑侦证据作为探索切入点的原因很简单,因为它无法做到像当代艺术理论那样对材料所呈现的内容与形式保留足够的宽容余地,它对于证据是否可信的判断会即时导向一个具体的结果,但这套仰仗理性操作的程序并不是总能做出正确的裁判。我们常常感觉到它们对于图像的理解是如此受限,或者说是有些许错乱在其中,恰似我们历史以来与摄影技术之间那些始终无法落地的纠缠。既想利用它摹刻和证明真实,又打心底里畏惧它对我们的隐瞒。或许摄影的本质确如莎丽・曼(Sally Mann)和罗兰・巴特(Roland Barthes )所说——它是一个接近于幽灵的存在,透明、飘渺、不可视也无从定义。

武雨墨, 透明攝影第十七張,溢出的溪流 (Spilling Brook), 透明摄影(The Transparency Photography), 2020

这也是我从武雨墨2019 年开始创作《透明摄影》(The Transparency Photography)系列开始,我在她的作品中逐渐发掘到的她对图像的个人领会。我想 「透明」 在这里并不是形容词,而是以名词形式出现是有原因的——并不是 「透明的」 摄影,而是摄影本身就是透明。

我们在这里提到的 「透明」 的概念与肯德尔・沃尔顿 (Kendall Walton)所认为的摄影是一种具有 「透视现实能力的媒介」 这一观点有本质区别,或者说它实际上更接近罗兰・巴特(Roland Bathes)在 《明室》(Camera Lucida)一书中提到的 「放射性物质」(Emanations)——它正在从明确的物理形态及意识形态中无限撤退,却始终为那些企图观看它的人带来困扰。正因为它给我们的是一种被文明所驯化的完美幻觉(Civilized code of perfect illusions), 这给摄影这门技术赋予了精神分析意义上的 「他者」(Other)的品质,摄影是为弥补和愈合欲望中那个永恒的伤口而生。

武雨墨, 透明攝影第十一張,颤抖的殘存像素 (Trembling Residual Pixels), 透明摄影(The Transparency Photography), 2020

武雨墨, 透明攝影第十一張,颤抖的殘存像素 (Trembling Residual Pixels), 透明摄影(The Transparency Photography), 2020在《透明摄影》(The Transparency Photography)和《错误照相片》(Photographs with Errors)中,身为 「照片」 本应诉说的形象意义被搁置,但作为 「图像」 极为突出的数码材料属性放大了它们的制作过程并将数码相机独特的媒介特质展露无疑。在摄影仍然处于银盐感光的时期,我们就见证了摄影师们对其媒介属性的革命性探索,以同绘画媒介的不可复制性相抗衡。回到如今的数字摄影时代,艺术家们就像苏珊・史都华(Susan Stewart)所说的那样开始对手工显像的独一性和工艺品质感到怀念(光是看看现在的照片调色软件有多么钟爱 「胶片感」 就明白了)从而抗拒像素图像的千篇一律和操作性上惊人的便捷...简而言之,这是对摄影技术趋向民主化与平民化的潜在恐慌。

武雨墨在这两个系列中却顺应着这样的操作转而放大数码摄影中的电磁质感,原本应该是高保真、高视觉转化率的图像在这里成为了 「错误的图像」 ——作为照片而言它是 「失败的」 ,因为它不能够清楚地传达出那种得以摹刻现实的直感性(Immediacy)以及可信性(Credibility),但它透过刻意营造的错乱直指向了当代摄影的另一种工艺模式。尤其是在电子材料质感上,我感觉到它们不仅并不拥有 「错误」 中常见的廉价钝感,反倒是惊人的细致与准确。图像经由计算机被处理的过程通过手动拦截而变得透明,原应作为整体出现的图像受此干扰遭到拆解和异化,变成了难以被直观解读的断层。

Catherine Yass, Descent: HQ2: ?s, 20°, 0mm, 4mph, south, 2003

Catherine Yass, Descent: HQ2: ?s, 20°, 0mm, 4mph, south, 2003卡瑟琳・雅斯(Catherine Yass)在2002 年创作的系列作品 《下降》(Descend)曾就类似的主题进行过探索,在911 事件的政治阴霾下,她利用扭曲、反转、颠倒、长曝光和物理剐蹭等手段拍摄的影像不可避免地带有一种悲剧性的色彩:我们是否还能做到在看见一栋新建成的摩天大楼的同时不去想象它落为废墟的景象?正如后摄影时代的我们在网络上面对电子图片的时候,还有没有可能将它视为一个独立的、不具备目的与指涉性的对象(又或者我们真的曾经有过吗)?

Gerhard Richter, Erschossener 1, 1988

进一步仔细观看,武雨墨的许多幅作品中依旧保留了可见的手工绘制痕迹,这一点不由令人联想到杰夫・沃尔(Jeff Walls)的 《障碍物》(The Stumbling Block)与葛哈・李希特(Gerhard Richter)的 《枪击》(Erschossene),前者是将多张编导过的 「纪实摄影」 通过电脑合成绘制的 「数字蒙太奇」(Digital Montage),而后者则是画家将刊登在报纸上的照片手工摹画下来的油画作品。这两幅作品的媒介全然不同,却同时表现出了身为图像对于被视为指示性符号(Indexical Symbol)的严词拒绝。

对武雨墨而言,这样的 「抗拒」 也是她创作的核心之一。她的照片中试图去展示的并不是任何对象,而是作为对象的摄影,与那些试图去凝视与解析它的观者。似乎只有当一件事物发生了故障和错乱,它内部真正的运行机制才有机会被揭露。 让・鲍德里亚 (Jean Baudrillard)认为摄影是一种 「完美的罪行 」(Perfect Crime),正因为它仅仅代表了我们欲见之物的表征,一个没有上下文的空洞的符号。如果我们去尝试揭开这一层意义,只会发现它所指向的虚无是经不起推敲的。

弗洛伊德的理论中对于 「错误」 有一番独到的认知,他认为对梦境或潜意识的解读永远都是碎片式的,在这些层面中精神分析师所阐释的往往是细节,而非整体。从一开始,他就将人的精神领域视为一种合成性的存在,这一点似乎能够引导我们更加深入地去理解武雨墨对于图像的态度。文章开头提到的图像作为刑侦证据的部分恰好说明了即便是最追求客观事实的科学,也难以回避 「透过假象进入隐含现实」 的陷阱。在摄影的历史中我们似乎总是在面对各式各样假象的挑战,无论是塔尔博特和尼埃普斯的时代还是杰夫・沃尔(Jeff Walls)与沃尔夫冈·提尔曼斯(Wolfgang Tillmans)的时代,它都是以可疑的方式在突破我们的认知,我们向摄影索求的真实仿佛一直被掩藏在暗房、计算机或是那些不能见光的原始文件当中。

武雨墨从2015 年开始就对 「负片」 的概念非常敏感,对于学习过胶片摄影的人来说,第一次在暗室里触摸到负片的实体其实都是颇为震撼,几乎带有一些宗教性质的体验,因为它经常被人认为是一张照片还尚未现形时的待定形态,而不是照片本身,这一点或许有点类似透过B超看见了胚胎的心脏在跳动的感受吧。乔夫里・巴钦(Geoffrey Batchen)在 《负像/正像:一部摄影的历史》(Negative/Positive: A History of Photography) 这本书中很深入地探讨了摄影史中负片与正片之间微妙的地位差异和互生关系,其中他引用了拉里·沙夫(Larry Schaff)的一句话 「从理化的角度而言,塔尔博特作品中的负片与正片之间并无本质区别;后者不过是前者的负片罢了。」 实际上不仅仅是塔尔博特,对于所有照片而言这种正负之分都是带有一种政治性偏见的。

武雨墨, 曬黑的痕跡(The Tanning Traces), 视觉的断裂(The Rupture of Vision)2021

人眼在看见负片的同时会屡次试图将它反转,在武雨墨 《视觉的断裂》(The Rupture of Vision)系列中的第一张照片里能够非常直观地感受到这种本能。第一眼我们看到像火箭一样拔地而起、带有突破形态的黑色粉末状物质,需要经过大脑的过滤才能意识到这是喷泉的水柱而不是爆炸带起的尘土。然而这张照片之所以令人惊愕,是因为它不同于其他的负片,它是一张乍眼看起来像正片的负片,两者的边界在大脑短暂的处理过程中被撤销了。

实际上,如果让弗洛伊德来解读正负片的关系,他会倾向于认为负片呈现的图像才是 「真实」 ,而那些被无限拓印的正片拷贝才是威胁所在。齐泽克说人类是唯一能够通过真话来行骗的动物,因为有些时候我们期望真话能够被当成谎言,这样一来我们便不必回应它的凝视。当我们必须要借助反转才能直面和识别一张图像时,应该对此感到警惕:非要如此阐释不可的动机是什么?我想这才是负片,乃至于任何被认为是 「错误的」 图像带给我们的本质意义。

所谓的数字艺术带来的伦理上的威胁,真的有如过去半个多世纪的想象中那样具有颠覆性吗?我们站在一个进退两难的节点——这是 「后摄影」 时代,但摄影的困境却好像从未被真正克服,也许应该换个方向撤退一步,再撤退一步,站在过去那些最原始的差错中去辩证和超越此刻它为我们带来的眩晕。

“The digital image", Sally Mann once suggested in an interview, "is like vapour that never comes to ground. It simply circulates, bodiless. It has no material reality".

From the very beginning of photography, the instinctive hostility of humans to this medium has been revealed quite directly: photographs, whether those that have attempted to show the quality of craftsmanship or those that seek to imitate reality in pixels, are difficult to trust. This seems to have formed a consensus that transcends the ages. But the relationship between people and photographs is by no means limited to this; under the right conditions, we still choose to take the presence of photographs or images as a criterion for determining tangible traces in the real world, while readily ignoring their potential pitfalls. In fact, it seems that a period of history with image records always has more privilege of being “remembered” than that without visual materials.

In the era of digital photography, the boundary between "photograph" and "image" has become more blurred. I attempt to observe this point from the research in the field of criminal investigation in recent years and find it very interesting. Among the eight types of evidence in the Criminal Procedure Law of China, the most decisive are physical evidence, documentary evidence and testimony of witnesses. They record either static facts or dynamic facts: permanent facts can only exist in objects and thus constitute physical evidence; transitory facts recorded by images are documentary evidence, while transitory facts perceived by people are testimony of witnesses.

In a general sense, images fall under the category of documentary evidence. In most cases, they are physical and are considered capable of objectively recording reality. However, with technological advances and inevitably diverse media materials, controversial evidence categories such as “audiovisual materials” have gradually arisen. These include audio and video produced by physical processes, electronic computer records, as well as “high-tech images” generated during case handling—so-called simulated images obtained with the help of laser, infrared, x-ray and other sophisticated instruments. On reflection, it seems that the "simulated images" mentioned are not "simulations" per se. (Aren't CT images of real bodies?) What they record is certainly a reality, one that we cannot penetrate with our eyes. Similarly, if shooting devices using laser and x-ray are considered sophisticated instruments, then cameras also have the same “high-tech” attributes to a certain extent.

Peruse papers in the field of criminal investigation in recent years, and one will find more similar sampling attempts presented with the help of new scientific techniques. One of the techniques mentioned in several papers is image stitching for the two-dimensional high-resolution acquisition of curved evidence surfaces. In this way, not only photographs and images, but also the relationship and the boundary between objects and images will change. Should this set of collected flat images finally be adopted as documentary evidence, physical evidence or audiovisual materials?

The reason for using criminal investigation evidence as an entry point for exploration is simple—it cannot retain sufficient latitude for the content and form presented by materials as contemporary art theory does, and its judgment of whether the evidence is credible leads instantly to a specific result. However, this procedure, which relies on the operation of reason, does not always deliver the right verdict. We often feel that its understanding of images is rather limited, or that there is a sense of ambiguity, just like the historical tangle that has always remained unsettled between us and photography. As much as we want to use photography for recording and proving the truth, we dread what it may conceal from us. Perhaps the essence of photography is indeed as Sally Mann and Roland Barthes have said: it is a presence close to a ghost, transparent, elusive, invisible, and indefinable.

This is also the personal understanding of images that I have gradually uncovered from Wu's work since she began working on "The Transparency Photograph" series in 2019. I think there is a reason for not using the adjective "transparent" here but the noun form - instead of "transparent" photography, photography itself is transparency. The concept of “transparency” we mention here is fundamentally different from Kendall Walton's idea that photography is a “supremely realistic medium”, or we can say it is actually closer to the “emanations” mentioned by Roland Bathes in Camera Lucida. It is retreating indefinitely from distinct physical forms and ideologies, yet it always bothers those who attempt to see it. Precisely because it brings us a civilized code of perfect illusions, photography is endowed with the quality of "other" in the psychoanalytic sense, which is created to mend and heal the eternal wound of desire.

In "The Transparency Photography" series, the figurative meaning of photographs is set aside, but the prominent properties of digital materials as "images" magnify their production process and reveal the unique features of digital cameras as a medium. At a time when silver salts were used in photography, we witnessed a revolutionary exploration for the properties of this medium by photographers to counter the irreproducibility of the painting medium. Fast-forward to today's digital photography era, as Susan Stewart put it, artists are becoming nostalgic for the uniqueness and craftsmanship of photographic films. (Just look at how many people favor the “film style" function in photo editing software these days.) They come to resist the uniformity of pixel images and the amazing ease of operation... In short, this shows an underlying fear of the democratization and popularization of photography.

In these two series, Wu follows this kind of operation to amplify the electromagnetic texture of digital photography. High-fidelity and high-resolution images turn out to be “wrong images” here — as photographs, they are “failures” because they could not clearly convey the kind of immediacy and credibility that can imitate reality, but they point directly to another process pattern of contemporary photography through deliberate confusion. In particular, when it comes to the texture of electronic materials, I find that they do not feature the common "mistake" of cheap bluntness but are instead surprisingly detailed and precise. The images processed by computers are made transparent by manual interception. They are supposed to appear as a whole but are disassembled and alienated by this disruption and turned into layers that are difficult to interpret intuitively.

Catherine Yass's 2002 series “Descend” explored a similar theme. Under the political haze of the 9/11 attacks, images she shot using distortions, reversals, long exposures and physical scratches inevitably had a tragic color: can we see a newly built skyscraper without imagining it falling into ruins? Likewise, when we see an electronic image online in the post-photographic era, can we view it as an independent object without purpose or indication (or did we ever have one)?

On closer observation, many of Wu's works still retain visible traces of hand-painting, reminiscent of Jeff Walls' "Stumbling Block" and Gerhard Ritcher's "Erschossene". The former is a "digital montage" that combines several edited and directed "documentary photographs" via computer, while the latter is an oil painting in which the painter drew a newspaper photograph by hand. The mediums of these two works are completely different, yet they both manifest a rigorous resistance to images being seen as indexical symbols.

For Wu, this kind of “resistance” is also at the core of her creation. What she aims to show in her photographs is not any object but the photography as an object and the viewers who attempt to gaze at and interpret it. It seems that only when something breaks down and goes wrong does the real mechanism of its inner workings come to light. Jean Boudrillard considers photography to be a "perfect crime" precisely because it is merely a representation of what we want to see -- an empty symbol without context. If we seek to unravel this layer of meaning, we might only find that the nothingness it points to cannot stand up to scrutiny.

Sigmund Freud's theory has a unique understanding of "mistakes". He believed that the interpretation of dreams or subconscious is always fragmented. In these levels, psychoanalysts often interpret details rather than the whole. From the beginning, he viewed the human spiritual realm as a synthetic entity. This point may guide us to understand Wu’s attitude towards images in greater depth. As is shown in the part of images as criminal investigation evidence mentioned at the start of this article, even the most fact-oriented science can hardly avoid the trap of "entering the implied reality through illusions". In the history of photography, it seems that we are always challenged by various illusions. Whether it's the age of Talbot and Niepce or the era of Jeff Wall and Wolfgang Tillmans, it's breaking through our perceptions in dubious ways. The reality we seek from photography seems to be hidden in the darkroom, in the computer, or in the raw files that cannot be seen.

Wu has been acutely sensitive to the concept of “negative films” since 2015. For those who have studied film photography, touching a negative for the first time in the darkroom is indeed shocking. The experience almost has a religious ring to it, as a negative is often perceived as the pending form of a photograph that has not yet taken shape, rather than the photograph itself. This is probably a bit like seeing the embryo's heart beating through ultrasound. In his book Negative/Positive, Geoffrey Batchen delves into the subtle differences in status and the symbiosis between negative and positive films in the history of photography. He quoted Larry Schaff as saying, “From a physical-chemical point of view, there is no essential difference between a negative and a positive in Talbot’s work; the latter is merely a negative of a negative." In fact, not only for Talbot's work, but for all photographs, the positive and negative distinction is politically biased to some extent.

When seeing a negative, human eyes will repeatedly try to reverse it. For example, you can clearly feel this instinct with the first photo of Wu's "The Rupture of Vision" series. At first glance, we see a black powdery substance that rises up like a rocket with a breakthrough pattern, and it takes a brain filter to realize that it is a fountain of water rather than dust brought up by an explosion. But what makes this photograph astonishing is that, unlike other negatives, it is a negative that at first glance looks like a positive, as the boundary between the two is withdrawn in the brief processing of the brain.

In fact, if Freud were asked to interpret the relationship between positive and negative films, he would tend to think that the images presented by negative films are "real", while the infinite positive copies are the threat. Slavoj Žižek said that humans are the only animals that can deceive through truth, because there are times when we expect the truth to be taken as a lie so that we don't have to respond to its gaze. When we have to use reversal to confront and identify an image, we should be wary of this: what is the motive for this interpretation? I think this is the essential meaning of what negative films, and indeed any image that is considered "wrong", brings to us.

Is the so-called ethical threat posed by digital art truly as disruptive as imagined over the past half century? We are on the horns of a dilemma—this is the post-photographic era, but it seems that the plight of photography has never been completely overcome. Perhaps it is time to retreat one step in a different direction, and then another, to stand in the most primitive mistakes of the past to analyze and transcend the dizziness it brings to us at this moment.